On Dec. 3, 2018, a 75-year-old woman sought emergency care at a hospital in Houston, where her treatment included blood transfusions. She was given two transfusions of the wrong blood and died after repeated cardiac arrests.

Investigating the incident

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services investigated the incident and issued a 99-page report that documented the issues that led to the patient’s death. The investigation determined that a label with the patient’s name was applied to a blood sample from a different patient who had been in the room previously. This mislabeled sample was sent to the lab and used to determine the type of blood the patient should receive. The room’s previous occupant had a different blood type, which resulted in the wrong type of blood being given to the patient.

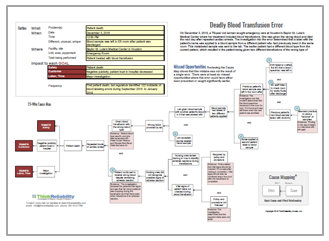

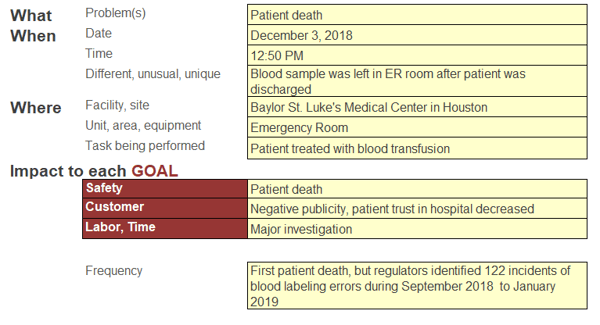

The report is long and dense, so a Cause MapTM, a visual format for performing a root cause analysis, allows us to intuitively lay out the report information to quickly show the cause-and-effect relationships that contributed to this issue. The first step in the Cause Mapping® method is to fill in an outline with the basic background information for the incident as well as list how the incident impacts the goals of the organization. An outline for this incident could look like this:

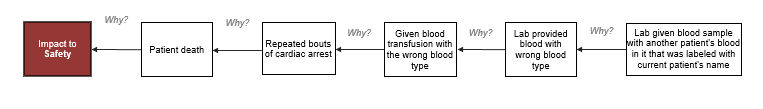

There are additional impacts that could be added to the outline, but it was kept relatively simple for this example. Once the outline is completed, the next step is to analyze the incident by building the Cause MapTM. Start with one of the impacted goals and ask “why” questions to begin. A 5-Why Cause MapTM for this incident could look like this:

Starting with five “why” questions is a good place to start, but clearly, more detail is needed to understand this incident. The Cause MapTM is expanded by continuing to ask why questions.

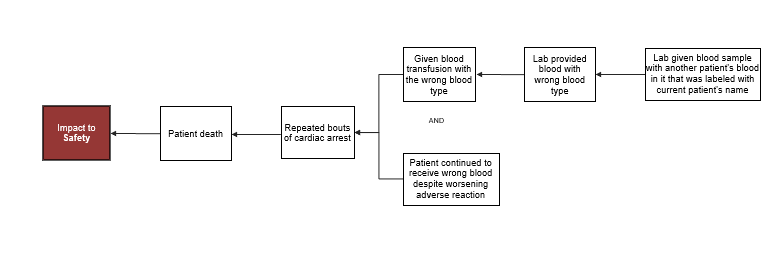

Cause MapsTM also rarely lay out in a straight line. A branch occurs when there are multiple answers to a “why” question (meaning there are two or more causes that contribute to an effect). For example, the report says that the patient suffered repeated cardiac arrests because she was given the wrong type of blood and that because the patient continued to receive the wrong blood despite worsening adverse reactions. If the blood type error had been identified sooner, and the patient had received a smaller amount of the wrong type of blood, and medical care had been provided sooner, then the outcome for the patient may have been better. When there is more than one cause that contributed to an effect, you add two cause boxes vertically and separate with an “and,” as shown in the diagram below:

To view the more detailed Cause MapTM, click on the thumbnail below. This intermediate-level Cause MapTM does not contain all of the report information, but it provides an overview of how the incident occurred and helps organize the information in a way that can be quickly understood.

Missed opportunities

Unfortunately, but importantly, the map shows the patient’s death was not the result of a single error. Most errors are caused by a combination of failures, and it is rare that a single error leads to an incident. There were multiple failures and at least six missed opportunities where this error could have been either prevented or caught earlier. Our Cause MapTM is limited to published information, but further research inside the hospital would be helpful to identify more areas where safety could be increased.

- The previous patient’s blood had been sampled without a doctor’s order because it was standard practice to draw a “rainbow” of blood samples (multiple tubes so multiple tests can be quickly done). This practice is necessary during emergencies, however, it opens the windows for mistakes to occur.

- The emergency department staff failed to check the room for left behind blood tubes after the previous patient was discharged. The investigation determined that the blood specimen remained in the room for more than 10.5 hours and was still present when the next patient was admitted to the room.

- The environmental services staff did not notify the emergency department that a blood specimen was left in the room. (Environment service staff cleans the room between patients, but is not responsible for disposing of blood specimens or tubes.)

- A nurse applied a second patient label to the blood sample that was left in the room. The report did not provide details about how the labeling error occurred, but it is against policy to double-label blood samples. It is possible that this is a human error, but further discussion with the nurse would be helpful to determine why this occur occurred.

- The lab accepted the double-labeled blood specimen. The lab is expected to reject samples that aren’t appropriately labeled. It is possible that this is was also a human error, but further discussion with the lab would be helpful to determine the details involved in the lab not following this procedure.

- The patient was given two different blood transfusions before the error was identified, despite a worsening adverse reaction that was not recognized. If the mistake had been identified more quickly, the transfusions could have been stopped and treatment could’ve been started much earlier, which may have impacted the outcome.

Previous incidents and near-misses

Rarely do incidents occur without warning, and this was no exception. In addition to describing the error that lead to the patient’s death, the report also identified 122 blood labeling incidents over a four-month period at the medical facility. Some of the incidents were more severe than others, but a few were significant near-misses. Just four days before the deadly blood transfusion error was made, the lab caught an error where a woman was nearly given blood ordered for another patient with a different blood type.

This is not the first time this type of error has occurred. Mislabeling specimens is a global issue. if you would like to learn more about this topic, you can read “Fixing the Problem of Mislabeled Specimens in Clinical Labs” or “Specimen Labeling Errors: A Retrospective Study.” You can also read “Right Patient, Wrong Sample” to learn about another near-miss wrong blood type incident, which includes findings and takeaways from the investigation.

It is always easier to see the warning signs in hindsight, but reviewing incidents of missed warning signs reminds us to look for patterns of smaller incidents and to take near-misses seriously. Ideally, a near-miss that had the potential to result in a patient death would trigger a robust investigation and an organization would take action to reduce the risk of another incident.

Working to improve

The hospital has been working to be transparent during the investigation and has issued statements about the changes being made to improve the reliability of their work processes and reduce the likelihood of a similar error occurring in the future. The executive leadership of the hospital has been replaced. The hospital has also announced plans to implement a policy that requires a stringent verification process in collecting and labeling blood specimens, adding additional safeguards in the lab to ensure improperly-labeled blood specimens are not accepted, improving recognition of blood transfusion reactions, among other policy and training improvements. While strict rules are a reminder of what not to do, it is always important to determine the systematic causes of an error in order to make a safer practice. Hopefully, the lessons learned from this tragic error will result in more robust work processes that reduce the risk of a similar incident occurring again at this hospital as well as other medical facilities.